“And I tell you also, that when necessary [the Mongols] ride full ten days without food, and without lighting a fire; but piercing a vein of their horse, they drink his blood. They have likewise their milk dried into a species of paste, which, when about to use, they stir till it becomes liquid, and can be drunk.” ~ Marco Polo via Rustichello da Pisa, The Travels of Marco Polo, ca. 1300

Disclaimer: I’m a white American dude who has never lived in a yurt or even been to Mongolia. Hey, I tried.

The quote above tells us a number of things about the Medieval Mongols of Kubilai Khan’s Golden Horde, the first of which is: they were pretty fucking tough.

It also hints at the centrality of milk and meat to the traditional Mongolian diet. The domestication of goats and sheep circa 6000 BCE enabled human beings to survive for the first time on the steppes of Central Asia, despite freezing temperatures (Mongolia is still home to Earth’s coldest capital city) and a lack of arable land. The domestication of the horse around 2,000 years later further eased this precarious existence in an inhospitable environment. Since animals were more valuable alive than dead on the steppe, meat was reserved for special occasions and long winters, with milk being the food of daily sustenance. It was made into butter, cream, yogurt, cheese and even booze, and dried into “instant” forms for long journeys as in the example above. UNESCO’s History of Civilizations of Central Asia states that cheese curd in various forms “had the same importance in the life of the Mongol population as bread has in the lives of farming peoples.”

By the time Marco Polo visited the Great Khan in the 14th century, a nomad’s wealth was measured in his animals: not only goat and sheep but horse, yak and two-humped camel, known as “the Five Jewels” (or, less poetically, the Five Snouts). In good times, Mongols lived off their herds, riding some of their living jewels and following the rest from pasture to pasture, eating milk and meat and sleeping in tents made from hide and felted hair. In hard times, a desperate Mongol could live off the horse he rode, falling back on wilderness survival tricks. The 11th-century Secret History of the Mongols, which tells of Genghis Khan’s humble beginnings, uses the future Khan’s boyhood reliance on hunted game to illustrate his family’s poverty. Later in the Khan’s life, when he led his armies on far-ranging campaigns, they brought livestock with them instead of supply trains. When conquering settled peoples, the Mongols intentionally destroyed farmland to return the land to its natural state, the better for grazing their animals.

In the centuries after the conquests of Genghis Khan, his royal descendants (“the Golden Womb”) would keep an opulent court influenced by the Chinese, the Persians and other peoples they had conquered. Yet even the cosmopolitan Mongol nobility never lost their carnivorous tastes. Genghis Khan’s grandson Kubilai drank the finest-quality airag (fermented horse milk) from a special herd of white mares, and dined on delicacies like baked strips of mutton fat and fried bull’s testicles, prepared with costly imported spices, wine, and vegetables.

Meanwhile, the Great Khan’s subjects in the Mongolian heartland continued to follow nearly the same lifestyle and diet as their ancestors. For many in Mongolia today, this ancient way of life continues. Modern nomads may use cell phones to check the weather and advertise homestays in their ger (yurt) on AirBnB, but they still scatter spoons of sacred milk on the wind in offering to Munkh Khukh Tengri, the Eternal Blue Sky. And they still survive on the Five Jewels, creating a unique cuisine that varies widely in form and flavor, if not ingredients.

THE RECIPE

There are numerous varieties of Mongolian cheese, but none of them are aged in the manner of European cheeses. There are two practical reasons for this. 1) When you’re a nomad, you generally don’t feel like lugging around big wheels of aging cheese from camp to camp with you, and 2) lacking other food sources, you can’t afford to wait weeks or months to eat something that’s technically ready to eat, now.

Eezgii (ээзгий) is one such milk product. It’s traditionally made from the first milk of spring, richer and fattier than milk produced later in the year, and is further distinguished from other curd dishes by its being roasted. The application of heat caramelizes sugars in the cheese, turning it brown and giving it a unique flavor while also drying the outside for preservation. My version is adapted from this recipe, from a great website with instructions on how to make traditional Mongolian foods (even boodog, which I swear I will try one day; a whole animal cooked inside its own skin with hot rocks and a blowtorch).

Cheesemaking begins with curdling, separating boiling milk into solid curds and liquid whey. In most Western traditions this is accomplished by adding rennet, a complex of enzymes naturally found in the stomachs of animals. Other traditions curdle milk with an acid like vinegar or lemon juice, the method used to make the Indian fresh cheese paneer. Mongolian cheese is curdled with the acid in kefir, or sour yogurt. Go no further if you’re lactose intolerant; in this recipe, we will be combining two dairy products to start a chemical reaction that will produce a third dairy product. It doesn’t get more Mongolian than that.

– 1/2 a gallon of whole milk (Fresh, unpasteurized milk is the best, but grocery store milk works too.)

– 1/2 a cup kefir (It can be hard to find a commercial yogurt sour enough to curdle milk. You can substitute full-fat yogurt and the juice of half a lemon. It’s not authentic, but it gets the job done, and you won’t taste the lemon in the end.)

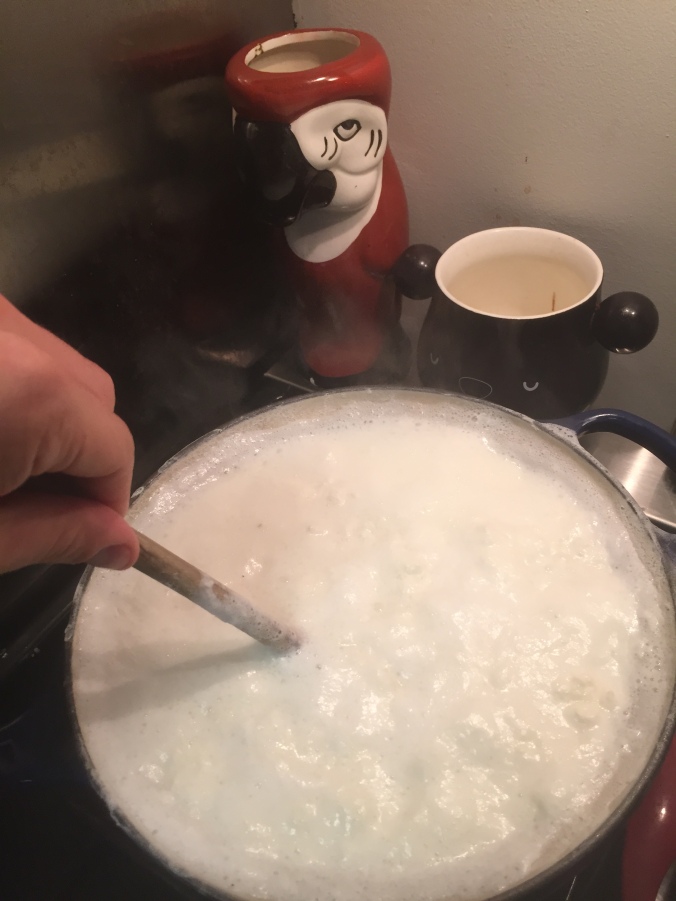

- In a large pot, bring the milk to a boil over medium heat. Stir frequently with a wooden spoon to prevent it boiling over.

- When the milk is boiling, add the kefir.

- Continue stirring until the milk is thoroughly curdled. You should see white clumps (curds) separated from translucent yellow liquid (whey).

- Remove from heat and strain out the curds. Save the whey! It’s full of nutrients and low in fat, and once it cools down, you can drink it or use it in tons of other ways.

- Return your solid curds to the pot. Stir them carefully over low heat until all the excess moisture has been cooked out and they start to look crumbly and very slightly yellow.

- Transfer the curds to a pan and bake at 300 degrees F for three hours. Remove and stir every half hour to prevent the curds from sticking to the pan.

Parrot mug and panda mug look on in approval as the milk begins to boil.

Shortly after adding the yogurt, we start to see some curdling.

Curdled af. The yellow stuff is whey, the white is the curds.

I’ve transferred the curds back to the pot and am now cooking out the excess moisture.

Before baking.

After three hours of baking, stirring, and general checking up, our eezgii is complete!

THE VERDICT

You wouldn’t necessarily know that eezgii was dairy at all. It resembles granola and has a crunchy texture and a lightly sweet, caramel-like flavor. The taste reminds me of brunost or mysost, a Scandinavian dairy product made from caramelized whey often called “brown cheese.” Having tasted aaruul (another form of dried curd) brought from Mongolia, the intensity of flavor and smell just doesn’t compare to what I was able to produce here. But my watered-down imitation nomad curd isn’t so bad, in the humble opinion of a non-nomad.

Eezgii doesn’t have to be refrigerated and will keep for a long time. Mongolians eat it as a snack, but I’ve also found it to be an interesting addition to other recipes. Try it in a sandwich or soup, or just pack some in your saddlebag to nibble on next time your tumen rides against the Khwarezmians. V out of X.

Before I leave for a vacation that will likely delay my next blog post, I’m excited to share a long-term project I’ve been working on: kamakh rijal, a kind of spreadable cheese from the Medieval Islamic world that’s incredibly easy to make. All you need is milk, yogurt, salt, and the courage to eat a dairy product that’s been sitting at room temperature for more than a month. My stomach feels fine, thanks.

Before I leave for a vacation that will likely delay my next blog post, I’m excited to share a long-term project I’ve been working on: kamakh rijal, a kind of spreadable cheese from the Medieval Islamic world that’s incredibly easy to make. All you need is milk, yogurt, salt, and the courage to eat a dairy product that’s been sitting at room temperature for more than a month. My stomach feels fine, thanks.

When I was visiting Paris, I ate a meal (okay, several meals) that consisted entirely of wine, bread and cheese. With this in mind, I spread some of my six-week-old kamakh rijal on bread and poured myself a glass of red wine. Not only did it go together well, it felt like a scene from a medieval Persian poem. “

When I was visiting Paris, I ate a meal (okay, several meals) that consisted entirely of wine, bread and cheese. With this in mind, I spread some of my six-week-old kamakh rijal on bread and poured myself a glass of red wine. Not only did it go together well, it felt like a scene from a medieval Persian poem. “

You must be logged in to post a comment.