“I behold the tilapia in its true nature, guiding the speedy boat in its waters.”

“I behold the tilapia in its true nature, guiding the speedy boat in its waters.”

~ From The Book of Coming Forth Into the Light, better known as The Book of the Dead, 2nd or 1st millennium BCE

In a prehistoric Egyptian tomb of the fourth millennium BCE, archaeologists unearthed a rare surprise. Unlike the carefully dissected mummies of later Egyptian history, whose innards were cleansed and removed to canopic jars, one of the bodies in this early tomb had its digestive system intact, complete with stomach contents. Analysis revealed the last meal of this early Egyptian: a simple soup of barley, green onion, and tilapia.

Today, tilapia has achieved fame for its versatility and economy as a food source. The fish breeds quickly in captivity, can tolerate cramped conditions, and eats almost anything plant-based, making it cheap and easy to farm. Its mild white flesh is inoffensive to palates unaccustomed to seafood and readily accepts a range of seasonings. After carp, tilapia is the world’s most-commonly farmed fish, riding a wave of popularity that took off in the 1980s and shows no sign of slowing down. But thousands of years ago in Egypt, the fish simply called in was already being raised in enclosed ponds and captured with nets and spears from the life-giving Nile River. The tilapia species most-commonly eaten today is still known, appropriately, as the Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus).

The Greek historian Herodotus remarked in 440 BCE how much the Egyptians cherished their animals. They let them sleep in their homes, mourned them when they died, and worshipped them as living gods. It’s no surprise then that the Nile tilapia was featured in Egyptian culture, art and religion as prominently as in the Egyptian diet. A popular shape for bottles and makeup palettes, tilapia was represented by its very own hieroglyph, ![]() . The fish was believed to help guide the Boat of the Sun as it sailed across the sky, as in the above quote from The Book of the Dead, a compendium of magic spells for ushering spirits to the afterlife. Tilapia was also associated with Hathor, the goddess of love and women, and considered a symbol of fertility and renewal. Such lofty significance may have stemmed from a misinterpretation of tilapia behavior. When danger threatens, the tiny baby fish swim into their mother’s mouth for protection (a phenomenon called mouth-brooding, also observed in other fish species). Ancient people who saw tilapia fry emerging from mom’s mouth may have believed the adult fish was miraculously creating the babies.

. The fish was believed to help guide the Boat of the Sun as it sailed across the sky, as in the above quote from The Book of the Dead, a compendium of magic spells for ushering spirits to the afterlife. Tilapia was also associated with Hathor, the goddess of love and women, and considered a symbol of fertility and renewal. Such lofty significance may have stemmed from a misinterpretation of tilapia behavior. When danger threatens, the tiny baby fish swim into their mother’s mouth for protection (a phenomenon called mouth-brooding, also observed in other fish species). Ancient people who saw tilapia fry emerging from mom’s mouth may have believed the adult fish was miraculously creating the babies.

Egyptians would not have recognized today’s supermarket tilapia, white, cleaned and vacuum-sealed. Not only did the Egyptians consume every part of the fish, they ate only the dark tilapia now referred to as “wild-type.” The color of a tilapia has no effect on its flavor, but because many modern consumers prefer white fish, commercial fisheries now rely on pinkish “red tilapia.” These fish have been selectively bred for a genetic lack of pigment called leucism, the same mutation which produces white tigers. And the modification of farmed tilapia doesn’t stop with their genes. Keeping these ancient symbols of fertility in mixed-sex groups leads to unmanageable population growth, so today’s farmers give the sexless baby tilapia food laced with hormones, causing most of them to develop into males.

THE RECIPE

This recipe is modified from Cooking in Ancient Civilizations by Cathy Kaufman (2006), one of my favorite sources for reconstructed ancient recipes. The original Egyptian stew this recipe was based on contained bones, fins and scales, but for the pictures above I was only able to obtain cleaned tilapia fillets. If you can find yourself a whole tilapia or a similarly mild white fish like catfish or sea bream, use it. As a wise woman (Maangchi) once said, don’t be afraid of fishbones, especially in soup! They add extra flavor, and when fish is properly cooked the meat falls off the bone easily.

This recipe is modified from Cooking in Ancient Civilizations by Cathy Kaufman (2006), one of my favorite sources for reconstructed ancient recipes. The original Egyptian stew this recipe was based on contained bones, fins and scales, but for the pictures above I was only able to obtain cleaned tilapia fillets. If you can find yourself a whole tilapia or a similarly mild white fish like catfish or sea bream, use it. As a wise woman (Maangchi) once said, don’t be afraid of fishbones, especially in soup! They add extra flavor, and when fish is properly cooked the meat falls off the bone easily.

Fish farms contribute to water pollution and the spread of fish diseases, but some have less of an impact than others. Tilapia farmed in the USA, Canada and Ecuador are the most ecologically friendly choice.

-1/2 cup barley

-3 cups water

-4 scallions/green onions, washed and sliced (use the entire scallion, including the root. The roots will give more flavor to the soup and will be removed before serving, taking another page from Maangchi’s book.)

-2 tilapia fillets or 1 whole, cleaned tilapia (or similar white fish)

-salt to taste

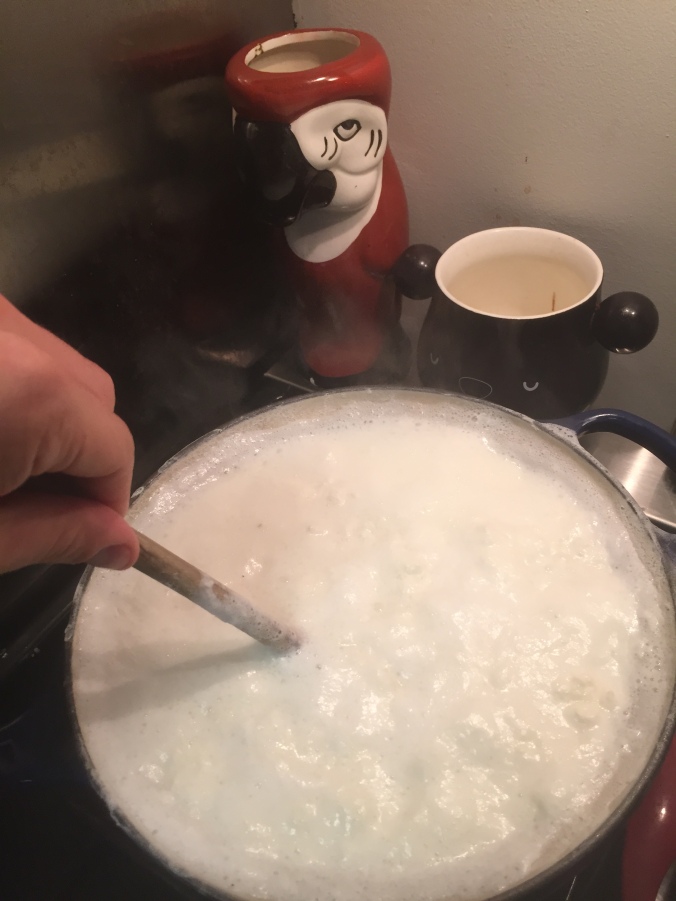

Rinse the barley and place in a saucepan with the water. Bring to a boil, add just the roots of the scallions, and simmer for 30 minutes. Use a spoon to skim off any foam that rises to the top (excess starch from the barley).

Remove the scallion roots. Cut the tilapia into chunks (if you’re using a whole fish, keep the skin, bones and fins). Add the fish to the water and cook for about 10 minutes over medium heat. Lower the heat, add the rest of the scallions and cook for 5 minutes more.

Taste and add salt as needed. Serve hot.

THE VERDICT

The fish releases some oil into the soup, and I find that it doesn’t need much seasoning to taste delicious, though you could also add garlic, butter or spices. It’s a simple, hearty meal that will have you landing solidly in Ancient Egypt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.