“Bread sprinkled with poppy-seed is mentioned by Alcman in Book V as follows: ‘Couches seven, and as many tables laden with poppy-bread, and bread with flax and sesame-seed; and in cups…chrysocolla.’ This is a confection made of honey and flaxseeds.”

~ Athenaeus quoting Alcman, Deipnosophistae Book 3 (early 3rd century CE)

Athenaeus of Naucratis is perhaps the greatest Ancient Greek food writer, though he lived and wrote in Rome at the height of its Empire. His masterwork Deipnosophistae (The Philosopher’s Dinner Party, among other possible translations) is an overview of Greek food culture that attempts to document just about every literary reference to food in Greek. In order to accomplish this ambitious objective, Athenaeus draws on a vast array of sources, not only food critics and chefs but poets and historians. He is nothing if not comprehensive: writing in the third century, Athenaeus recorded a reference to a sweet called chrysocólla (χρυσοκόλλα) in the work of Alcman, a poet who lived about a thousand years earlier, in the 7th century BCE.

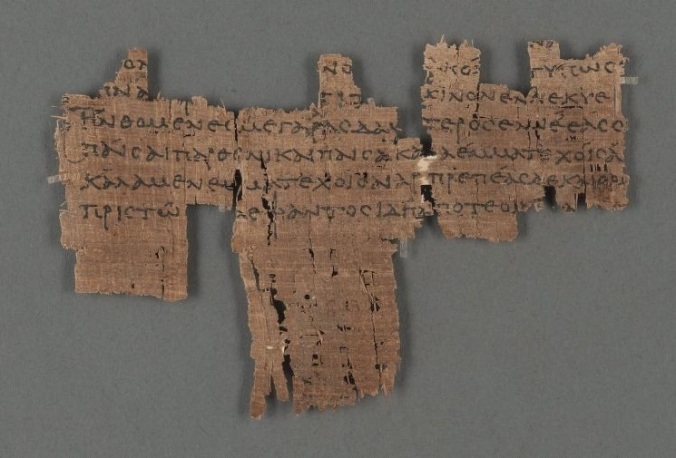

A papyrus fragment from Greek Egypt, now in the collection of the Louvre in Paris, with one of Alcman’s poems. Alcman’s Greek combines features from different dialects, possibly further evidence that he was not a native speaker. Public domain (2011).

Lighthearted and celebratory, Alcman writes often of the joys of food and his own great appetite, even calling himself in one poem ho panphágos Alkmán, “the all-devouring Alcman.” Yet we know that he lived in Sparta, that most austere of Greek cities, whose other poets are far more serious and grim. An ancient tradition maintains that there was good reason for Alcman’s un-Spartan ways: he wasn’t Spartan, or even Greek, by birth, but came from Lydia in modern Turkey. The poet himself seems to support this claim with a remark that he learned poetry from the chukar partridge, a Near Eastern bird that is not native to Greece. According to Aristotle, Alcman arrived in Sparta enslaved, but his master freed him because of his remarkable poetic ability. He would go on to be listed with literary rockstars like Sappho and Pindar among the Nine Lyric Poets, those deemed most worthy of study by later Greek scholars. Evidently, it pays to listen to partridges.

Alcman called the chukar kakkabi, after its three-note call. It would probably enjoy this recipe (at least the flaxseeds). Photo from Wikimedia Commons (2004).

In Ancient Greek, chrysocolla means “gold glue.” Alcman’s confection shares the name with a striking blue mineral that was used as solder by ancient goldsmiths, gluing the precious metal together. From the name and ingredients, we can infer that Alcman’s chrysocolla was a crunchy hard candy, resembling the sesame pasteli of modern Greece, the amaranth tzoalli of the Aztecs, and similar seed and nut candies enjoyed around the world. Deipnosophistae itself contains a reference to another ancient version, a Cretan specialty with both sesame and nuts called koptoplakous, from a word meaning “cut off” or “broken” (compare English “brittle”).

Today this type of candy often contains sugar refined from sugarcane, a plant which was unknown in Greece until 326 BCE, when Alexander the Great’s men returned from India with stories of “the reed which gives honey without bees.” The genuine honey in this recipe is enough to bind the flaxseeds together. The added olive oil helps keep the gold glue from sticking to everything else.

THE RECIPE

-1 cup honey

-1 cup whole flaxseeds

-Olive oil

First, toast the flaxseeds by placing them in a dry skillet over medium heat. Stir continually for 5-7 minutes, until the seeds are glistening and start to jump around in the skillet. Remove from the heat. Oil a glass or ceramic dish and set aside.

In a saucepan, bring the honey to a boil while stirring with a wooden spoon. Once the honey is boiling, lower the heat, stir in the toasted flaxseeds and cook for an additional 15 minutes, continuing to stir.

Remove from the heat and spread the mixture onto the dish, smoothing it as much as possible with the back of a spoon. Let cool for 1-2 hours in the fridge, until it has set into a hard, amber-like candy. Snap the chrysocolla into pieces and place in cups.

Alcman described himself as an indiscriminate eater, but it would be hard to find anyone who would turn up their nose at this sweet, crunchy treat made with just three ingredients. Sometimes the simplest recipe can bring the greatest joy, a principle of cookery which Alcman well understood.

“And then I’ll give you a fine great cauldron, wherein you may gather food in heaps. It’s still unheated by fire yet, but soon it’ll be full of that thick stew that the all-devouring Alcman loves, piping hot when the days are past their shortest. For he eats not what is nicely prepared, but demands simple things like the common people.”

~ Alcman quoted in Deipnosophistae Book 10

You must be logged in to post a comment.